Who started design thinking? And where is it heading? In our Long Read, Clive Grinyer charts the growth of design thinking from a niche activity to a mainstream practice. Pulling examples from the worlds of technology, public sector and finance, Clive argues that we need design thinking and designers more than ever.

The evolution of design thinking

There’s no birthday for design thinking. Despite important landmarks and significant claims and contributions from designers, projects and agencies, there was no big bang. In the old days, the term “design thinking” described the techniques and methodologies employed by designers to create abstract services and experiences. Now, it’s much broader in scope and application.

Design thinking was present a long time ago in my design education. The system of analysis and synthesis, sketches, computer renderings and models made in workshops was all about customer insight, concept creation, prototype-building and testing. These are the same processes and techniques that nowadays we call design thinking.

But in my very first job, I noticed that the business world was actually very disconnected from customers and design practice. Design briefs focused on features and market research instead of user insight and testing. Unconscious decisions were made, resulting in marketing that over-promised and an operationally focused customer service.

The spread of Design thinking

Geoffrey Moore’s Law of Technology Adoption describes how an initial idea is spread by visionary early adopters. The idea traverses the “chasm” of slow adoption and then grows dramatically when those applications and contexts show evidence of success.

Design thinking became established with the spread of design practice. When the pioneering agencies began to talk about service design and design thinking, early adopter organisations were quick to see the benefits. Economies moved towards creating value from services as well as products.

But for many years, design thinking remained the domain of the early adopters, because it was seen as threatening traditional, expert-based thought. It wasn’t until we created sustainable service and design thinking practices and the mainstream started believing that such “soft” techniques actually worked that design thinking took off.

Fast-forward to the last decade and suddenly tech services such as IBM launched its design thinking methodology and recruited 1,000 designers worldwide. Since then design thinking has become ever more deeply integrated in business at a strategic level from large multinationals to the smallest start-up. A highly successful international design industry now delivers user centred service design, research and delivery and has become an important integrated element within companies and organisations.

Design thinking…in technology

Technology is an obvious application for design thinking. As a central part of our lives, technology has to be accessible, usable and appropriate to people other than the clever few who developed it. During my time at Orange, Cisco, the techniques of design allowed me to shape strategy and deliver technology projects.

For Orange, usability and beauty was a driver of revenue, not a “nice to have.” And at Cisco, creating empathetic, user-informed technology solutions shaped the core technology that it developed for its customers. This helped companies see the real business benefits and allowed them to successfully exploit the scale and reach of technology. The future of digital transformation, the inviable enablers of AI and Blockchain and the connected world of the Internet of Things is as much about trust and customer approval as it is about big data and networks.

…In financial services

The interest in design methodologies in business has been phenomenal. I was as surprised as anyone to find that at Barclays, design practice and design thinking are at the heart of how they developed digital banking services.

Barclays initially set up a centralised design office that developed a series of industry-leading products including the first peer to peer transaction platform Pingit and the first versions of the Barclays Mobile Banking, which led the way in digital banking. Design became truly integrated into every business – and designers were in great demand.

But with digitisation comes opportunity to do more than designing screens. Deconstructing processes, removing bureaucracy, putting the user at the heart of process and designing their service experience all changed the nature of how they engage with customers.

At Barclays, design thinking and service design effected product strategy, resolved complex complaint issues and became deeply embedded into the mindset of management.

…And in the public sector

It’s a lesson learnt by government too. The revolution that was the setting up of Government Digital Service transformed many aspects of life in the UK. The Policy Lab was also set up with the very purpose of using design thinking tools to shape effective legislation and practice.

For the public sector, design thinking has been particularly attractive and at odds with traditional practice. Whether it’s obesity or mass transport, engaging with societal problems and driving real behaviour change is tough.

Customer empathy

I am amazed every day at how keen business leaders and managers are to use the tools of design and user research in projects and strategy. And it’s no fad. In a post-innovation world, where blindly pursuing new ideas is no longer the primary objective, empathy with customers comes top of the list.

We need emotional context to create clearly differentiated brand experiences that are simply more beautifully designed. This demand often comes from younger generations of employees who are frustrated with old corporate ways of doing things. And, of course, from customers, who increasingly articulate their thoughts and criticisms via social media.

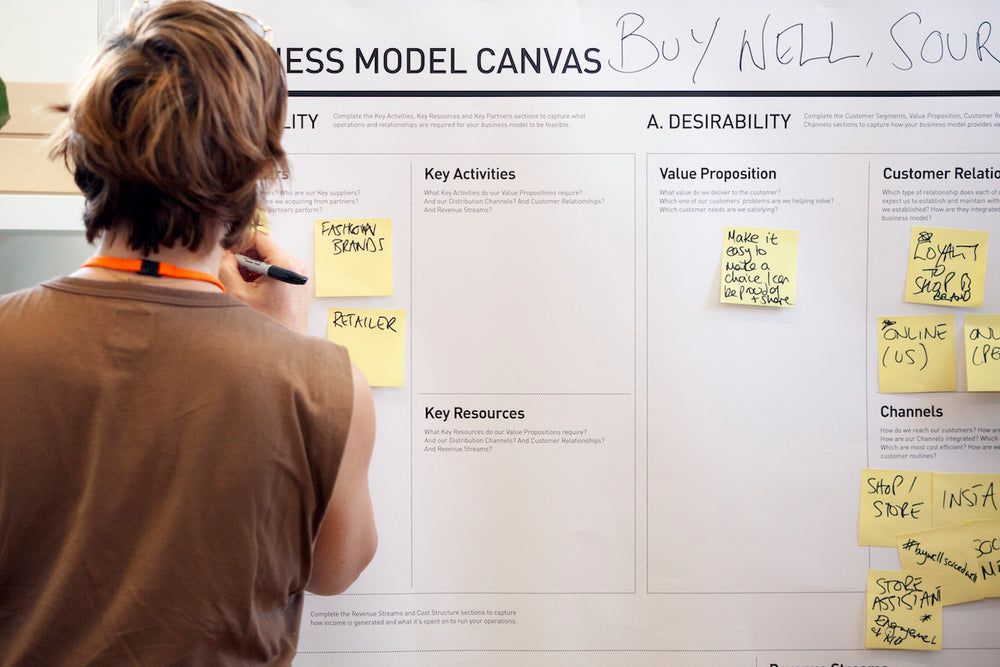

Prototyping ideas Design’s interest in deep user insight, rather than mass research, can therefore offer great value. The same goes for tools such as co-creation and prototyping. By piloting prototypes, you gain feedback and catch problems early in the process. In this way, design has the potential to impact on the success of an initiative or policy.

So, we’re surrounded by success and the embracing of design. Job done? Mission accomplished? No.

Are we all designers now?

This is an important moment in the journey of design thinking. Great progress has been made. We’re fed up that so many aspects of our lives have been designed by accountants, marketeers, technicians or policymakers – those who care more about revenue, message, technology or politics than our real needs and desires. Design offers tangible benefits that complement, orchestrate and deliver human value.

But this is just the beginning. Tim Brown, CEO of IDEO, is often cited as the creator of design thinking (though he’d agree that we’d all been doing it anyway). In a speech at Central Saint Martins in London, Tim noted that business school students were great advocates of design thinking and a more creative, empathetic approach to management.

There’s great value in demystifying and sharing the tools of design. But it’s also vital to know when a higher level of skill and design thinking processes is required.

Designers are different

A designer will see things differently from an accountant or a technology creator. In creative workshops, business students would come up with a single concept and be happy with it, whereas a design-trained student would create five and iterate each idea before finding the ultimate solution.

In a world fascinated by processes that promise responsiveness and rapid development, as exemplified by agile, the role of the designer becomes ever more important.

The designer is a facilitator, a champion of human empathy and a guardian of quality and simplicity. Designers override organisational or technical decisions that can chip away at the customer’s eventual experience. It’s collaboration between all parts of the organisation that makes great design happen.

It’s time to love design

There’s also a perception that design thinking and associated activities like service and customer experience design are somehow weak when it comes to aesthetics. But this should never be the case.

Now is the time to raise our ambition. The outputs of design thinking should be as beautiful as we can make them. They should be loved and treasured by all who use them. Rarely does this cost more, though it can take time to find talent and allow it to flourish. The results are always worth it.

Now that we love design thinking, it’s time to love design. Design of the detail, the delivery, the communication, the feel and the experience. People know design is their right and not a luxury; it’s merely humankind deciding how to make things as good as we can make them. This can be applied to an exceptional health service. Or to a transport system that’s empathetic to those who live around it as well as those who use it.

Design is the ultimate shared human activity, by us, for us. It’s time to love design, not just on its birthday, but every day.

(This article was originally written in 2015 and has been updated by Clive in November 2022)