Design has its own particular culture, just as business does. And so do ‘sub-cultures’ like 1970s punk rock. This might sound like the start of a corny joke, but what would happen if a punk rock band, an anthropologist and a couple of MBAs walked into a bar? And how does it help organisations to solve problems? Ezri Carlebach sets off to find the punch line.

When you walk in to Central Saint Martins in the Granary Square development at King’s Cross, you notice that there’s a ‘vibe’ – an air of ‘coolness’ – of mostly young people wearing distinctive clothes, sporting stand-out hair-dos, and generally looking hip. "There’s a sort of grooviness," agrees Professor Lucy Kimbell, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, adding that "we don’t even have the words. You and I are old, so we say 'groovy', but young people would say something else, god knows what! But there is a culture that is discernible."

Attempts to define ‘culture’ can lead to lengthy debates, so for now let’s go with anthropologist Clifford Geertz, while forgiving his gender-specific language, when he wrote, ‘Believing, with Max Weber, that man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun, I take culture to be those webs.’

Taking our cue from Geertz, the way people behave and dress, the attitudes they display, and the sense of what’s permitted or approved of, constitute the "webs of significance," or the material and symbolic elements of a culture. It’s long been axiomatic in business that "culture eats strategy for lunch" (attributed to the late Peter Drucker, although no exact source can be found), and the value of culture was firmly recognised in the 2016 Financial Reporting Council publication Corporate Culture and the Role of Boards. Urging businesses to take culture seriously as a governance issue, the report states that "a healthy corporate culture is a valuable asset, a source of competitive advantage, and vital to the creation and protection of long-term value."

Pretty vacant

With its art school heritage, including famously hosting the debut public appearance of punk iconoclasts the Sex Pistols, Central Saint Martins still seems to carry an element of rebellion and novelty in its culture. Kimbell agrees: "It’s a culture that rewards and celebrates making new stuff. The drive for the new. But with many of the complex problems we face, I would question whether we need new thinking. There are already many solutions and different kinds of thinking being tried out, they’re just not necessarily available or obvious to the people who have the possibility to make decisions and make investments."

This leads to the apparently contradictory, yet increasingly likely notion that the art school ethos of a place like Central Saint Martins has much to offer the suited-and-booted style of the modern corporate machine. Professor Kimbell has been teaching design thinking to MBA students for over ten years. She is also part of the team launching a new MBA, as a partnership between her institution and Birkbeck College.

The new course puts creativity and design at the heart of business management training. "To be an effective manager or future leader, you need to be able to explore things creatively with other people," says Kimbell. While playing down any competition with the big MBA brands such as Wharton, Harvard or Oxford, Kimbell says the new joint CSM-Birkbeck course focuses on a futures-orientated offer that will help a new generation of organisational leaders to "explore problems and find solutions in the open-ended but nonetheless systematic way that design thinking offers."

Writing on these pages earlier this year, Matt Spry – a consultant, and graduate of our Design Thinkers Bootcamp – agrees. "A dynamic environment means that agility, adaptability and creativity are increasingly important attributes for every organisation, regardless of sector or size," he writes, before going on to explain eight specific dimensions to the design thinking journey that organisations need to consider.

For Kimbell’s part, as Director of the Innovation Insights Hub at University of the Arts London, including Central Saint Martins, her remit is to generate and develop solutions for business challenges, social issues and public policy questions. This involves building cross-disciplinary consortia and teams to bring creative approaches, including design thinking, into academic research and the treatment of complex problems.

If the kids are united…

The question, then, is how do organisations identify challenges and address them? How does society do it? How do policy-makers do it? "These are core questions for our times," Kimbell concurs. "The challenges are really pressing, in every area of life."

Looking at this from a neuroscientist’s perspective, Robert Burton wrote in Aeon magazine that "social problems are fantastically complex, while human minds are severely under-engineered," and that, as human beings, we need to acknowledge our serious "cognitive limitations" before leaping to the mostly wrong conclusion that, whatever the problem, it’s someone else’s fault. Perhaps design thinking can help, and Kimbell seems to think so.

"It offers a really accessible, simplified, and usable way of helping a group of people in an organisational or cross-organisational setting go through a process of coming up with ideas and moving them onward in a way that’s participatory and open."

Kimbell talks about design schools as being "studios for society," which of course includes start-up businesses, hospitals, multinational corporates, schools, voluntary organisations and all manner of institutions. In that context, she sees design thinking as being something like a simplified version of the studio-for-society concept. Many people in the business world now recognise design thinking as being a potentially valuable tool for unlocking innovation, but to some the distinction between design thinking and design as a practice remains unclear.

"My experience of life tells me that children are creative – but they’re not designers," Kimbell points out. If a child’s instinctive creativity is at one end of a learning curve, then design as a professional, competent capability is at the other end. "In the middle is a set of specific skills that can be taught," she notes. "That’s design thinking, and that’s what Central Saint Martins and Design Thinkers Academy both teach. Those skills force you to think about how you explore and structure problems as well as generate solutions." In turn, these lead to innovation insights.

In Kimbell’s view, there are many practices associated with design in all its diversity and richness, and design thinking is one version. "The version that the Design Thinkers Academy or IDEO do, makes some of the cognitive and symbolic capacity of design – some of the culture of design – available to other people who might not come from that tradition."

Some organisations already work in that way, notably in the start-up and technology sectors where the demands of digital transformation have encouraged divergent strategies. They don’t necessarily call it design thinking, but they enact versions of it. But most organisations, and most managers tasked with driving innovation and ensuring performance in those organisations, could use a little help in that direction.

Something better change

Inevitably, there are complications. In two articles published in the journal Design and Culture, Kimbell urges us to "rethink design thinking." She stresses that there are different ways of understanding what design thinking is, and identifies three distinct paradigms: first, while it’s not possible to know what actually happens in the mind of a designer, it is possible to posit design thinking as a cognitive style which is externalised and articulated; second, it can be an organisational problem-solving methodology; and third, it is part of a tradition of design research.

The Design Thinkers Academy draws on elements of the first two paradigms, offering organisations a way to develop innovation as a practice. There are other versions of design thinking in use: "There’s the NHS version, which is called EBCD, or experience based co-design, and similar versions in US healthcare systems, and now there are versions of it in the policy space too," Kimbell adds. "It is inspiring that those things have emerged, where practitioners in a particular field have developed a version of something that looks like design practice for their context."

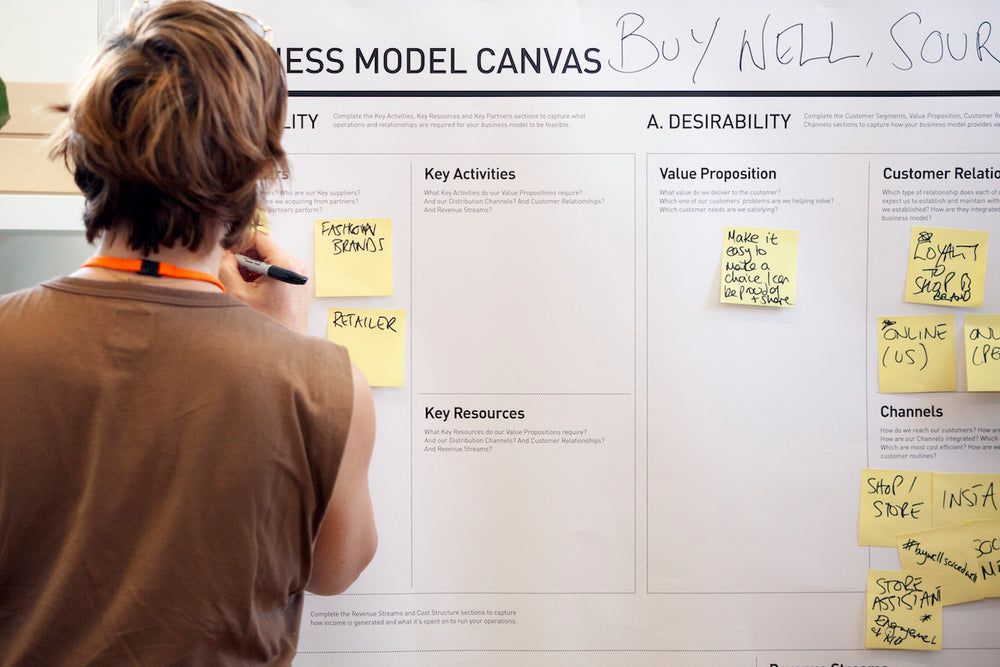

However, design researcher Jeroen van den Eijnde sounds a cautionary note. "These days, concepts such as design thinking and design research are presented in many policy plans as a remedy for entrenched notions, group thinking, and tunnel vision in the business world," he writes. Acknowledging that the expected result is an improvement in organisational innovation, he warns against rote applications of design thinking that lead to "mindlessly sticking coloured pieces of paper to a board during brainstorm sessions." That would clearly be missing the point, and a negation of the rich design culture that forms the totality from which design thinking is an excerpt.

Perhaps what’s needed then is a mindful approach to design thinking. Mindfulness is about developing the ability to recognise that we are thinking, and while mindfulness practise is based on not directing – or designing – your thoughts, design thinking can be viewed as a tool for adding some necessary structure to our thinking, preferably at the point when we begin to search for innovative solutions to existing challenges, or to create entirely new opportunities for ourselves and our businesses. Like walking into a bar with people from completely different backgrounds and cultures, design thinking can help us to recognise new situations as opportunities, not threats.