Steph Cutler founded her inclusion consultancy, Making Lemonade after experiencing unexpected sight loss. She participated in our last Design Thinkers Bootcamp to further her work with clients in facilitating courageous and wide reaching outcomes. Here she shares how inclusive approaches often lead to innovative solutions.

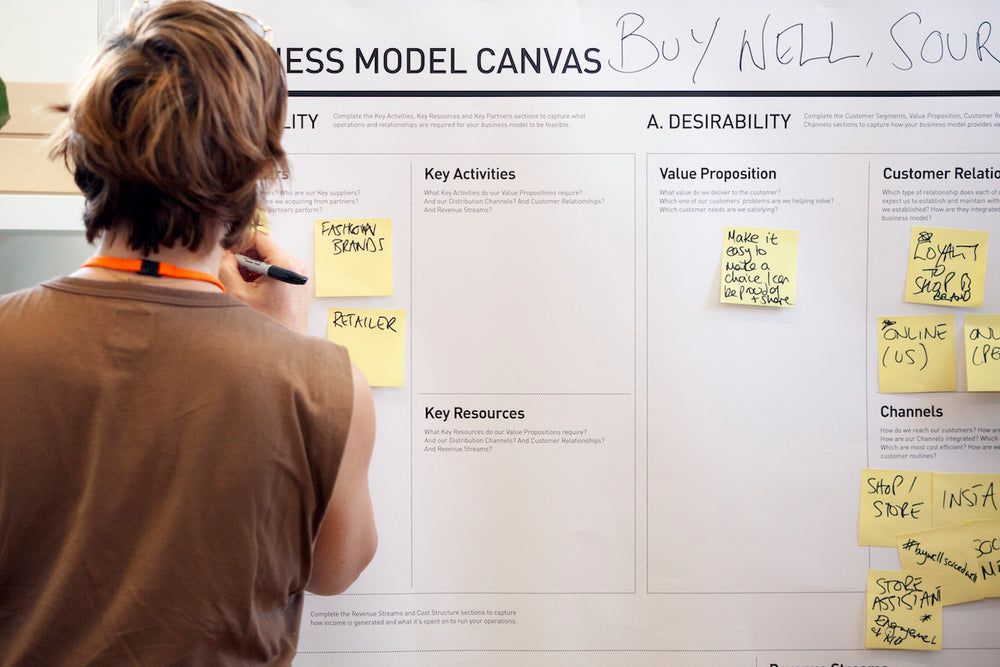

I was recently part of a team working on a challenge posed by the Design Thinkers Academy London and the NHS. At the start of the service design process, we all conceived a persona of a patient for whom the challenge effected. When we reviewed our personas, it became very apparent that we had all created someone who was not a million miles from ourselves and the world we inhabit. They were all relatively privileged, had similar aspirations, were au fait with the digital world, and had a supportive partner or friends. It is hardly surprising that we chose to design a solution for a person we could relate to. As human beings, we naturally group ourselves by likeness, rather than difference.

I therefore decided to propose a new persona who was nothing like us, which was adopted by the group as the one we would seek a solution for. Life was harder for her: she could barely afford the latest technology so her understanding of the digital world was limited. She needed the service we were designing as much as any of the other customers we had created profiles of, but she almost got left behind from the outset.

Critical to knowing who you are designing for is to include those who are on the periphery, as well as those who make up the centre ground. Why so? Because an idea that suits an extreme user will almost always work for the mainstream majority.

"An idea that suits an extreme user will almost always work for the mainstream majority."

Everyone can probably see the logic in this, and we all know we ought to be inclusive, but as a designer this might not set you on fire! Well, perhaps it ought to! I challenge any assumption that being inclusive means dumbing down, or putting a damper on creativity. In fact, it’s often quite the opposite.

I have lost my central vision so I literally see things round the edges! Being partially sighted means I problem-solve all the time. Trust me, I don’t always want to be problem solving – it’s exhausting, but it is my everyday. Moreover, it is usually because people like me have not been considered in the service design process. Regardless of the reasons, it means my reality is about adapting frequently, and accessing things differently. Sometimes that ‘different way’ provides really valuable insights that would go unnoticed by a sighted team member.

For me, losing a sense means I take in information differently. I rely on my hearing more than I did when I was sighted; I detect emotions through tone of voice and pace and pitch; I am much more aware of silences and I notice what’s not being said more than I ever did before. This doesn’t elevate me to a higher plane than anyone else. It makes me equal but different, and both ‘equal’ and ‘different’ are important. I don’t read non-verbal communications such as gestures and facial expressions as well as I did. The difference is that, within a team, most people can do both reasonably well. As I can’t do one particularly well, but do the other especially well, I add a different way of contributing – just by being me.

Before my sight loss I would have slotted nicely into the mainstream. As a disabled person, I now fall into the extreme. In my experience, the perspective on the periphery is more interesting and enlightening. It invites uncomfortable conversations; and innovative outcomes develop from those conversations.

Design thinking is, in part, about changing perceptions of how a product or service needs to operate. Who better than the people who do it differently to help you design it differently? If we are all saying the same things to the same people, where is the creativity going to come from?

I can’t look straight ahead, but in my view too many people focus on the obvious which is directly in front of them and miss the best bits. The edges are the most interesting places; made up of some of the most interesting people. Actually, I think my sight loss is one of the least interesting things about me, but it does give me a valuable design thinking perspective.

"The edges are the most interesting places; made up of some of the most interesting people."

I have found that ‘periphery people’ are much more likely to be honest, and more inclined to challenge others. I’ve been on the end of this and it’s not comfortable, but it can really move things forward! ‘Periphery people’ find themselves on the extremes – mostly from exclusion rather than choice. They are typically more honest as they have nothing to lose.

I had to challenge my perceptions and approaches big time when I went from being a sighted fashion designer to a blind unemployable twenty-something. However, my life is now enriched by working differently, and with people not considered mainstream. So, how can you challenge your perceptions?

For starters, here are a few simple suggestions:

- Extend who you follow on Twitter and ‘like’ on Facebook. Include people you don’t actually like and who don’t share your views.

- Engage with the customers your complaints department are having to deal with. If you get it right for the people you can never seem to please, the rest of us will be delighted.

- Rethink your recruitment practices. Include people in your design teams, and the customers you seek feedback from, who don’t look or sound like you.

- Push back when the personas being created are reverting to type. – Reach out to communities you never hear from and you have never invited in. Engage with them at the research and prototyping stage and you will have insights you could never have foreseen.

- Be courageous and start listening to people who don’t tell you what you want to hear

Engaging with ‘periphery people’ might just turn out to be the magic ingredient in the creative process. They might just be the keys to unlocking the elusive ‘unknown unknowns’